By Emily-Rose Njonde

Posted on January 14, 2022

There have been four-thousand dead and 700,00 Cameroonian Anglophones displaced in the last five years, that we know of at least. Since 2016, Cameroon’s Anglophone minority has been waging the fight of their lives in order to stay alive. Children have been killed, schools burned down, men and women assaulted and kidnapped, living under constant threat and fear. Cameroon has been recognized by genocide watch as having demonstrated the 10 stages of genocide. And yet, you’ve probably never heard of it.

Crash course

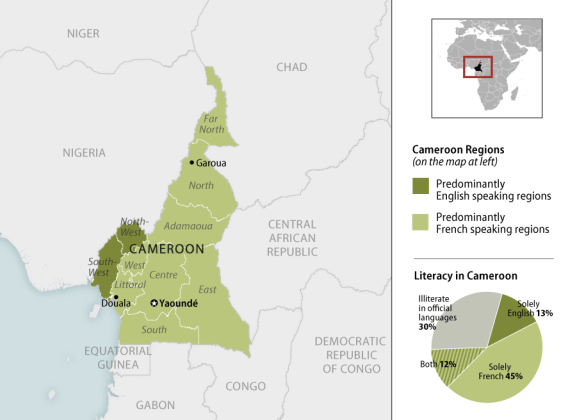

Cameroon is a country in central Africa comprising eight Francophone regions (in light green), and two Anglophone ones (in dark green). This division is the result of the colonial legacy left by the British and the French who colonized the country after the German defeat during the first world war. During this time, the languages, justice system, education system and social norms practiced in the two areas completely diverged.

The British inherited what was then referred to as Southern Cameroon and practiced a system of indirect rule, allowing traditional chiefdoms to stay in place and promoting self-government, however, their rule was also neglectful. Contrastingly, the Francophone land was directly administered by France. Thus, France’s political, legal and social norms shaped the country. While limited, greater industrial and infrastructural development took place and created a less democratic environment than their British counterparts.

The subsequent reunification of the two regions can account for the basis of the anglophone crisis in Cameroon. After a long civil war, Cameroon’s French regions obtained independence on January 1,1960. The Anglophone sectors however were never given the option of independence. Because developing countries stated that the Southern Cameroons would not be economically stable, the only options provided were for them to join Cameroon or Nigeria. It was only a year later, on February 11, 1961, in a UN-supervised referendum that the South decided to join Cameroon, whereas the North joined Nigeria, a change that was formalized on October 1, 1961.

Another important thing to note about Cameroon is that since its independence in 1961, there have only been two rulers: Amadou Ahidjo (1961 – 1982) and Paul Biya (1982 – Present), both using authoritarian regimes. Ahidjo appointed federal inspectors for each region who had to report back to the federal president. In West Cameroon (the Anglophone regions) this federal inspector had more power than the elected prime minister of the region. He also did things such as change the currency to the FCFA that reduced Anglophone purchasing power by 10 percent. In 1966 the one and only Cameroonian political party, The Cameroon National Union (CNU) was formed and all others were dissolved. When Biya took power, the move towards “centralization” resulted in the assimilation and marginalization of the Anglophone community that is still seen today.

Crisis

The beginning of the current crisis dates back to October 11, 2016 in Bamenda when Anglophone lawyers went on strike due to their demands being ignored by the Ministry of Justice. They wanted the use of Common Law in the North and Southwest regions and the English translation of legal texts among other sensible demands. In November of the same year, the lawyers organized a march with hundreds of people to invite the government to take their demands seriously. The march, beginning as a peaceful event, was interrupted by violent gendarmes who manhandled and arrested participants. The teachers were the next to go on strike and had a rally that attracted several thousand people. Once again, the police and the army violently dispersed the group, beating and even shooting civilians, a report confirms that at least two people were shot dead. The protests then spread across the region and got increasingly more violent. Between October 2016 and February 2017, at least nine were killed and many more sustained gunshot wounds. Those arrested appeared in military court under the terrorism law and security forces are constantly being used to intimidate the public. Prominent Anglophones such as Supreme Court Abine Ayah were arrested on charges of funding the Anglophone campaign. Despite the unfounded charges, Ayah has since remained in prison.

The Cameroon government has repeatedly failed in their “attempts” at pacifism. Constant unsuccessful negotiations, police abuse and riots, and yet the government refused to acknowledge the existence of a problem. As a response, On January 9, 2017 the Cameroon Anglophone Civil Society Consortium organized “Operation Ghost Town,” a two day complete shut down in which everyone, from children to adults, stayed home. This practice carried on into what is now called Country Sundays: every Monday and national holiday everybody stays home. After the successful shut down, the government retaliated by shutting down the internet on January 17 and arresting the Consortium leaders. They were left for 92 days without Wi-Fi, while the government continued to make claims about the Anglophones simply being extremists. Despite making certain changes, they still did not meet the concerns of the trade union. This constant disappointment caused the formation of extremist Anglophone separatist groups. The violence from both sides is increasingly dangerous and constantly puts civilians at risk.

During the past year, while there has been a decline in battles between separatists and armed forces, there has been an increase in attacks against civilians. Government forces are raiding villages, burning homes and killing civilians. A military raid in Mautu resulted in many murders, including that of a child. In Bali, security forces destroyed over 50 homes and killed several. They’ve damaged health facilities, opened fire in public markets, destroyed public and private property along with an innumerable list of despicable actions. This is no longer a political crisis but a humanitarian one.

Help

The people of Cameroon need help. “Around 1.9 million people, about half of whom are children, are estimated to be in need, an increase of 80 per cent compared to 2018, and an almost 15-fold increase since 2017.” Children are constantly living in fear, 85 per cent of schools are non-operational or closed and when they are open, students face the possibility of being kidnaped en route. 40 percent of health centers have been closed and so, amidst all the violence, many are left suffering and untreated. As of today, the country has only received 27 per cent of the funds needed to enact the Cameroon Humanitarian response plan. Other than the U.S., Cameroon’s other Western partners such as Canada have not made any public statement, despite being aware of the current circumstances.

People are dying. If we claim to be a nation that cares about life, and freedom, then we must help them. Down below are some sources to further inform yourself about the crisis and help make a difference.

Further Reading:

https://anglophonecrisis.carrd.co/?ltclid=68f3256a-4711-4e12-8e3c-0b6bfa58d352#LearnMoreà

https://www.washingtonpost.com/graphics/2019/world/cameroon-anglophone-crisis/

https://www.britannica.com/place/Cameroon/Moving-toward-independence

https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2020/country-chapters/cameroon

https://www.dw.com/en/cameroons-anglophone-crisis-no-end-in-sight/a-56106405

https://www.genocidewatch.com/single-post/2020/08/10/genocide-emergency-cameroon

https://news.un.org/en/story/2019/11/1050611

https://reports.unocha.org/en/country/cameroon/