By Priscilla Wiredu

Posted on December 17, 2021

Most people have not heard of Henrietta Lacks, a Black woman known as the “immortal medical marvel.” However, her story left a remarkable impact on modern-day medicine and science as we know it. Her family fought to get her name recognized in medical history and to receive justice for the way she was used as a lab rat against her consent or knowledge posthumously.

This article will discuss the life of Henrietta Lacks: her story, her family’s fight, and how her tale is an example of the importance of ethical medicine and informed consent.

Background

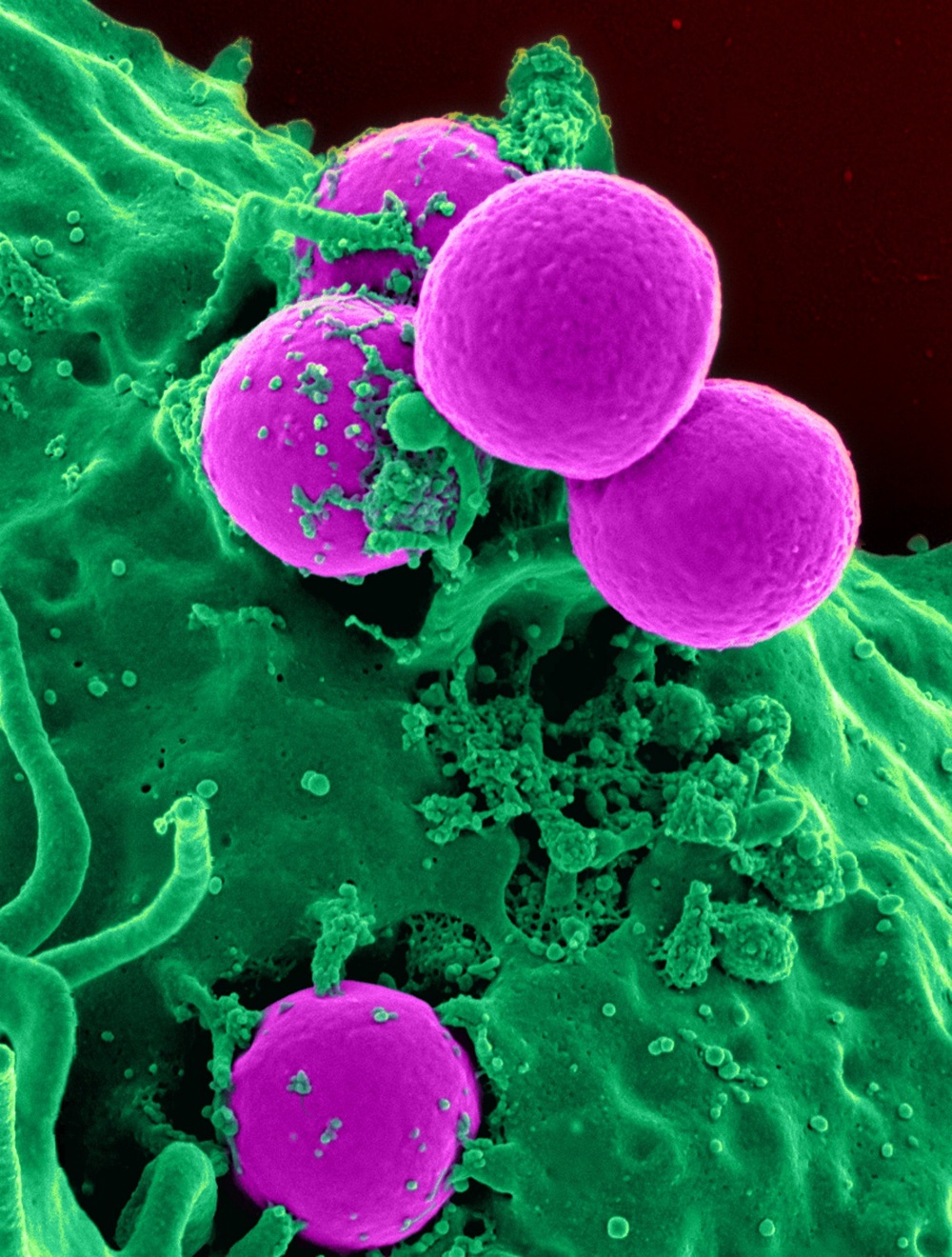

Henrietta Lacks was born on August 1, 1920, as Loretta Pleasant in Virginia to Eliza Pleasant and John Randall Pleasant. At an early age, she became a tobacco farmer but had to stop working to support her family by age 12. She married David Lacks in Virginia on April 10, 1941, after having two children. The devoted Catholic couple then moved to Maryland so David Lacks could work at a steel plant. Henrietta Lacks then birthed three more children. In January 1951, Lacks went to John Hopkins Hospital to have a doctor examine a knot in her womb, which was later diagnosed as cervical cancer. Unbeknownst to her, the doctor did two biopsies, taking a sample of both her cancer cells and her healthy ones. The cancer progressed rapidly and Lacks ultimately died in October of the same year. Her cells were kept in a lab by cell biologist Dr. George Gey. The said cells were able to survive and reproduce outside a body host due to a mutation. Dr. Gey became intrigued by this and began continuously growing the cells for further experimentation.

These cells were named after Lacks, known as “HeLa” cells and were used in many medical experiments due to their ability to grow outside the human body. HeLa cells were said to help the development of the polio vaccine, in-vitro fertilization, the first cloning of a human cell, gene mapping and much more.

As impressive and pivotal as these cells were in the creation of modern-day medicine, neither Lacks nor her surviving family received any recognition for her cells until the year 1975. This was the result of racial bias and sexism, and a prime example of how medical studies targeted Black people as unwilling test subjects rather than human patients seeking options for health management and treatment.

Racism and sexism

The HeLa cells have reaped incalculable profits over the decades, yet it was not until much later after Lack’s death that her family knew about this, and even later when they were given the right to consent to the use of her cells. The story of Henrietta Lacks illustrates racial inequities embedded in Western society and healthcare systems. The family received absolutely no compensation for the use of her cells and were not even notified about having her name published as well as her medical records and cells’ genome for public access. Her family finally was able to reach an agreement with the U.S. National Institute of Health in August 2013. A new agreement stated that Lack’s genome data will be accessible to those who apply for and are granted permission. Additionally, any research publications that use that data are required to include an acknowledgement to the Lacks family.

Lacks’ case exemplifies the treatment of Black people throughout history, how harvesting their organs and body parts had become a more privatized practice since the Emancipation Proclamation and the Civil Rights Movement. Black bodies are seen as study points rather than patients needing healthcare, and findings are seen to help the public in the future and advancement of medicine. It should be known that while what they did with Lacks’ cells was legal, it was a breach of privacy for both Lacks and her surviving family, as well as a violation of doctor-patient confidentiality.

The creation of Black Lives Matter as well as bringing awareness of the unfair treatment of Black communities during the COVID19 pandemic has encouraged scientists to reconcile with past racial injustices. There have been debates on reducing the use of HeLa cells or stopping its use completely, stating that using the cells without the owner’s consent is unethical and begs the question of a human’s individual rights versus the common good of the society. Lacks’ family, which has descended into dozens of members over the years, launched a new effort to call for people to remember her and celebrate her legacy and life. They want people to know Lacks was more than just cells: she was a woman who did everything she could for her family. She was someone’s daughter, wife, mother, and deserved to at least have her name remembered in history.

Aside from racism, sexism also comes into play. Lacks, being a female, most likely did not receive many options for treatment of her cervical cancer, alongside not consenting to having her bodily autonomy compromised (i.e. the biopsies in which the cells were taken). She was not treated properly for her cancer since it was seen as terminal, and was instead a test subject until she passed away. Black women are often depicted as containing the “Mitochondrial Eve” gene—a common gene that relates all living humans to one ancestor. Black women’s bodies have been used for decades for Western society’s benefit through sexualization, surrogacy, fetishization or even studies or experiments on the human body. These are all done without Black womens’ consent.

The story of Henrietta Lacks teaches us about the ethical trade-offs the scientific communities deal with when pursuing something in the name of the common good, and it can be a cautionary tale. We can now voice concerns about ethical treatments and demand appropriate measures to be taken to learn from past mistakes.

Success so far and future endeavours

Thanks to years of fighting in her name, the National Institute of Health (NIH) has made it law that funded research on the HeLa cells requires approval by a board that consists of two Lacks family members. Lacks’s grandson, Alfred Lacks Carter, finds it amazing that HeLa cells helped advance cancer research, fitting since Henrietta passed from aggressive cancer. He received many letters from people who were able to conceive children via in-vitro fertilization thanks to the help of HeLa cells. He believes that while it was unfair of her to have her cells stolen, it helps many people of many ethnicities across the world.

For the past decade, scientists and the Lacks family collaborated to establish stricter rules to govern the use of specimens. However, much work still needs to be done.

The first issue is action on consent. NIH director Francis Collins signalled that he wants the research community to consider changing the Common Rule; the set of policies that protect human participants in research funded by the United States government. Such a revision would require consent obtained from any patient that has had biological specimens taken and the samples are used in research, which also includes “deidentified” persons.

While initially failing in 2017, the Common Rule is once again going under review to reconsider the question of consent. Some researchers in the past warned that this could add on more burdens and that a compromise must be found. The last time the Common Rule was changed, a series of other changes had to be taken into consideration as well. One theory is to tackle the question of consent for biospecimens themselves with thorough discussion involving scientists and the public.

Another step must be to acknowledge and undo the disparities that are baked into basic research—because the systemic racism that existed when Lacks’s cells were taken still exists today.

In the current climate of reckoning with racial injustice, some researchers who use HeLa cells have concluded that they should offer financial compensation. For example, a laboratory at the University of California, San Diego, and a UK-based biomedical company have announced donations to the Henrietta Lacks Foundation, which was established in 2010 by Rebecca Skloot, the author of a book about Lacks. The foundation awards grants both to Lacks’s descendants and to family members of others whose bodies have been used without consent for research. Other institutions and researchers must examine whether—and how—their own work builds on past injustices and consider how best to make amends.

COVID-19, a virus that is disproportionately affecting Black people in a number of countries, offers an opportunity for those who wish to usher in a fairer era of research. To give back now, researchers should not only study why the disease is more prevalent and severe among Black people but also help to implement solutions to close the gap. The recent COVID19 vaccines—which were a result of working with HeLa cells—can help marginalized communities with protection.

The fact that Lacks’s cells were taken in a different era of consent will never justify what happened. The past cannot be undone, but we must acknowledge the wrongs of previous generations, and those wrongs that persist today. Justice must be achieved, and the time to start is now.

Priscilla Wiredu is a writer for this year’s Black Voice project. An alumni of York University, she graduated with Honors where she studied Social Sciences. She then went on to get an Ontario Graduate certificate in Creative Writing from the Humber School for Writers, and a college certificate in Legal Office Administration at Seneca College. She is currently studying for the LSAT in hopes of going to law school. Her main goal as a Black Voices writer is to ensure Black issues and Black Pride are enunciated through her works.