By Veracia Ankrah

Posted on September 24, 2021

Black existence is rendered political. Our hair is a topic of discussion, generating enough opinions to have Black peoples banned from several workspaces and children suspended from school. Our essence reigns with a very particular swagger that you and I can’t describe but know exists. All these parts of our global Blackness show up in our art and, unfortunately, as marginalized, underrepresented peoples, we sometimes find difficulty in critiquing Black art. Black art is an expression of our world and needs constructive criticism from the very people that not only consume the crafts but view it through a cultural lens informed by shared experiences.

There are far more white critics that work at popular publications, like The New York Times, credited with propelling entire careers or causing a film or album to fail, even if they are tasked with critiquing art forms they are not knowledgeable of or lack context for. At some point, these critiques were valued more than the court of public opinion found on social media, but now anyone can create like-minded discourse about art. A couple of viral tweets or TikTok videos of one’s review on movies and new music add perspectives, positive or negative, and can generate viewership and attention to various works. If we fear that publicly critiquing Black art will hinder our chances of creating more art in the eyes of white-washed media, we are allowing the same gatekeepers we wish to abolish influence our expression and creativity—a pleasure they’ve enjoyed for far too long.

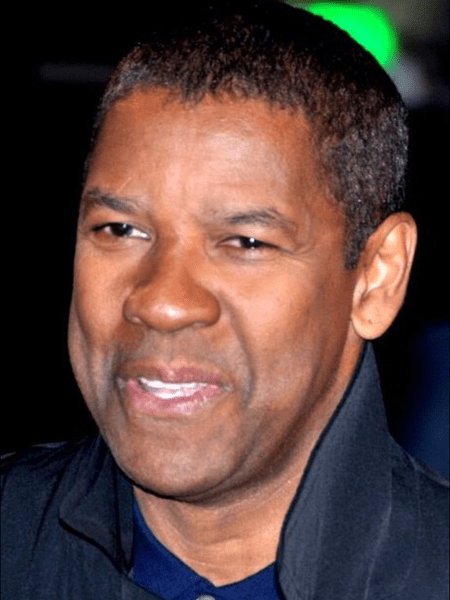

When Denzel Washington, the director and actor of the most recent adaptation of Fences, centring an African-American family in the 1950s, was asked why the film needed a Black director at a SiriusXM interview, he responded, “it’s not colour, it’s culture.” He explains that although Martin Scorsese directed Goodfellas and Steven Spielberg directed Schindler’s List, either of them could have directed either movie well enough but the cultural context is what makes those movies come to life for viewers outside of that world. This rationale applies to all areas of Black art. There are subtle cultural differences that only people from a specific background can pick up on and translate on-screen, to use Washington’s example, like the way a hot comb feels or smells like on a Sunday morning.

In a 2019 piece “If You Want to Protect Black Art, Protect Black Critique” written for The Root by creator and critic Tonja Renée Stidhum, she dissects the negative reaction Black women critics received when they share their occasionally unpleasant opinions. “The assumption that black art cannot handle critique is patronizing, condescending and far more insulting than any negative review will ever be. And no one can critique art created by Black people with the nuance, firm tenderness and thoughtfulness of a black critic,” she writes. Right around the time Stidhum was moved to speak on Black criticism, Lena Waithe’s Queen & Slim caused an influx of varying opinions on the polarizing film. Some loved the unorthodox display of two dark-skinned leads in an on-the-run love story while others weren’t fans of racially charged protests in tandem with a passionate car sex scene. Both critiques are valid and will contribute to the film’s discourse for years to come, in a way that pushes the bar for further Black filmmakers and, at the very least, provides varying opinions.

Neo-Soulstress Erykah Badu once proclaimed, “I’m an artist, and I’m sensitive about my sh*t.” I’d assume these sentiments are widespread for Black artists and, as Black consumers, we must continue to critique fairly and earnestly for the benefit of our beautiful, meticulous art forms. Nothing benefits from praise alone, and Black art deserves the potential to grow to its greatest form as long opinions are honest and beneficial rather than simply malicious.